Sara Murphy, Savannah Beacon

In the last 12 years, the Charlotte-Mecklenburg region has suffered severe job losses in manufacturing and textiles exacerbated by insufficient economic diversification, coupled with increasingly higher housing prices. The area also exhibits persistent patterns of racial segregation and ongoing struggles with upward intergenerational economic mobility.

Laudably, Charlotte-Mecklenburg is one of the few regions in the country that has named these challenges explicitly and demonstrated a clear intention to address them. Its Leading on Opportunity plan, a comprehensive framework to close racial gaps, reduce segregation, promote economic mobility, and pursue shared prosperity provides a model for other regions to follow. Leading on Opportunity’s focus on child and family stability, early care and education, and college and career readiness emphasizes the imperative of elevating the cross-cutting factors of segregation and social capital as part of a regional economic development strategy.

The Charlotte-Mecklenburg region is itself a part of a larger regional collaboration. The Centralina Regional Council was created to serve the needs of a nine-county region, working at the regional, community, and individual levels to shape area-wide planning. One of Centralina’s key successes was CONNECT Our Future, a framework built on consensus across two states and 14 counties to guide and invest in the region’s growth.

Michelle Nance, planning director at the Centralina Regional Council, said elected officials’ leadership was key to Centralina’s success. “It started when we were deemed one of the fastest growing regions in the country with no growth plan,” Nance explained. “Elected officials from across the region realized that if they wanted to sustain the benefits from growth, they’d have to manage it.”

Nance emphasized the importance of understanding and accepting that the 14 Centralina counties are not the same, having different needs and barriers. That said, there are also common threads, which became Centralina’s core priorities. Each community implements those priorities in ways most appropriate to them.

Regionalism works best for needs that cut across multiple areas, like transportation. “Gridlock isn’t business friendly,” Nance quipped, “and if we’re going to invest in our infrastructure, it should be done efficiently. Everybody doing their own thing isn’t efficient.” Regional collaboration not only cuts down on the administrative burden and cost of a given program, but also helps to attract federal dollars. “Agencies want to see everyone on the same page,” Nance observed.

It’s also critical to engage all stakeholders, and not to rush that process. “We learned to do things on a slow bake,” Nance said. “Take the time to build consensus. We call it ‘harvesting the worries.’ We make sure everyone is heard, because you don’t want something coming out of left field when you’re 75 percent done with a project.”

While Centralina is deeply ingrained within its communities, local officials know their people best, so Centralina leans on them as critical interfaces between regional efforts and the individuals they serve.

“We make sure our town managers, planning directors, and heads of economic development planning commissions are well versed in our projects and have communication materials to take back to their constituents,” Nance explained. “We don’t have to take center stage for a project to be successful.”

The greater Dallas-Fort Worth (DFW) region faces common challenges, including traffic congestion and problems with equity and digital inclusion. The region is less typical in its immense sprawl and permeable borders that people frequently cross for daily activities. As such, coordination across localities on service provision makes sense, and a number of institutions work on various aspects of regional coordination.

The North Texas Innovation Alliance (NTXIA) works collaboratively to improve quality of life, foster inclusive economic development, and increase resource efficiency using data and technology. NTXIA convenes 21 founding members, including 12 cities, a variety of councils and alliances, and the DFW International Airport to help connect cities, the private sector, academia, and trade schools. It plans to establish strategic advisory committees to tackle complex topics including data standards and privacy, cybersecurity, digital inclusion, financial models, and procurement.

Jennifer Sanders, NTXIA’s executive director, says having an independent, non-profit entity running regional efforts is effective in corralling resources and providing focus without risking allegations of favoritism. It all starts with core champions.

“For us, it was a nucleus of 10 agencies and cities that were passionate about the need for a regional approach,” Sanders said. She hammered home the indispensability of involving all sectors of society and clearly defining the mission, and noted the importance of being honest about barriers, such as procurement and funding.

“Regions need to find sustainable financial models,” Sanders emphasized. “Stop relying on a five-year bond cycle. Think about securing private equity funding. If you’re working on a large infrastructure project – which is exactly the kind of thing where regional approaches are effective – collaborate on buying agreements and requests for proposals (RFPs) on infrastructure design deals.”

Sanders highlighted the importance of data-sharing across regions, noting many municipalities don’t fully understand the problems they face without the broader view that comes from pooling information. Consider an extreme example: The authorities had no idea the Golden State Killer’s murders were connected because they didn’t share information. Sanders recommended an instrument called inter-local agreements (ILAs) to help structure data-sharing arrangements.

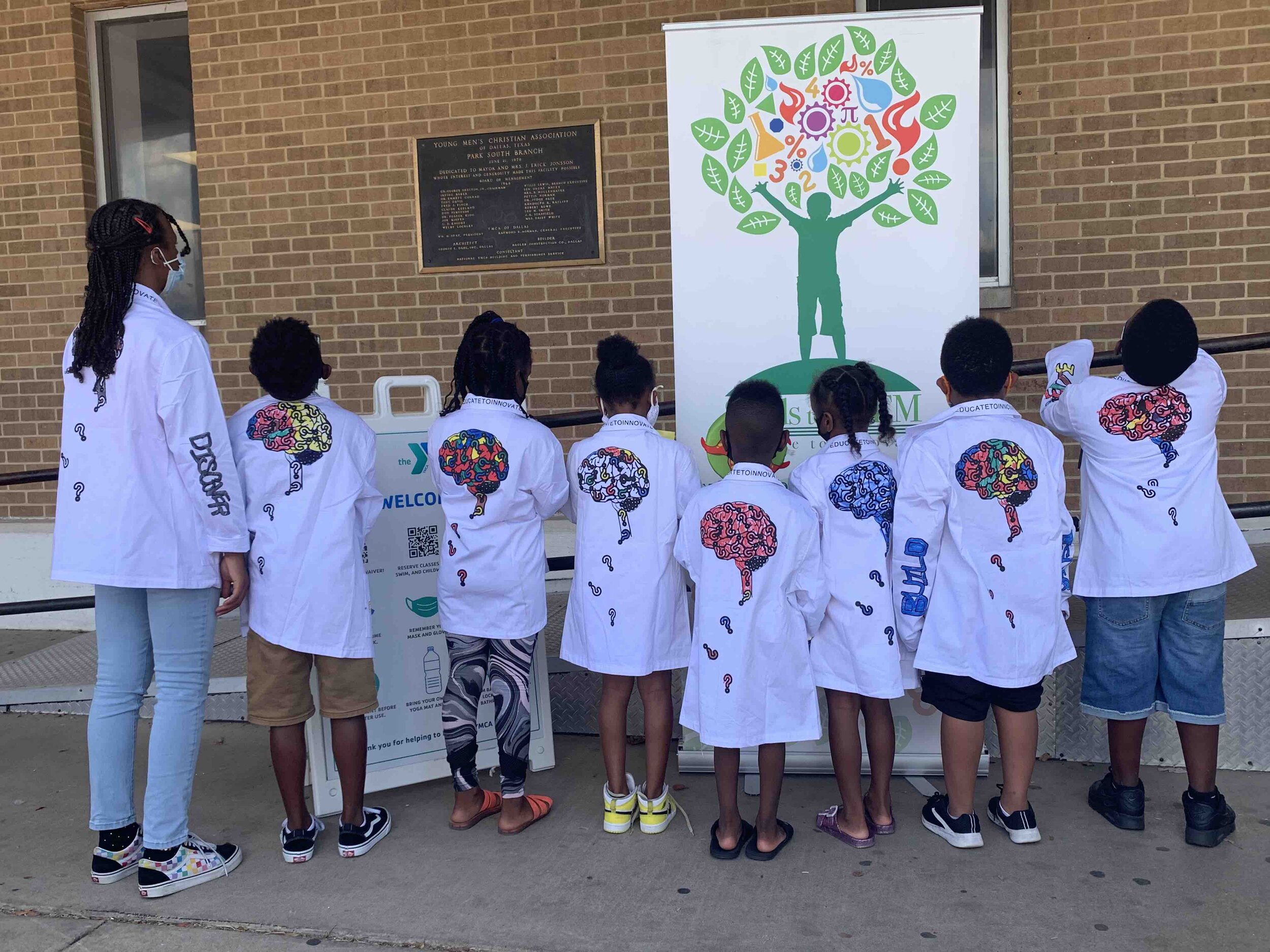

Educate Texas works with communities across the state to establish and implement strategic and measurable community-specific action plans and to ensure resources are directed toward developing innovative programs or scaling evidence-based practices that lead to better outcomes. The group recognizes that cross-sector collaboration within communities is key to the creation and support of an aligned pipeline between K-12, higher education, and the workforce to support students’ success in school, work, and life.

Chris Coxon, Educate Texas’ managing director of Programs, said regionalism is a mindset. “Whatever issue you’re trying to take on, no one entity is going to be able to turn the ship, and certainly not to accelerate to the level of progress the broader community expects.”

Coxon emphasized the importance of clarity around an initiative’s goals and how they’re measured. “What does success look like?” Coxon asked. “Answering requires some degree of data and analytical acumen, but also an ability to translate that to a publicly digestible message. If you can’t get someone off the street and explain your work to them in simple terms, you’ve lost.”

Asked how to engage the public school system in regional collaborations, Coxon said they have to see that the players are truly there to help. “Most often, school districts are leery of actively engaging in these types of initiatives because it’s just about, ‘Let me show you more data on how our schools are failing our children,’” Coxon observed.

In the Rio Grande valley, Educate Texas brought together two non-profits with school superintendents and university presidents. “Initially, the non-profits started tearing into the school districts,” Coxon said, “and we had to tell them, ‘No, the purpose here is to find solutions, not to take pot shots.’” Successful collaboration means working together to achieve shared goals, and it requires slow trust-building.

Leadership North Texas (LNT) is a graduate-level leadership program aimed at recruiting, developing and supporting leaders who have a commitment to civic engagement, learning, collaboration, and the DFW region. Participants learn best practices in regional stewardship from other successful regions and participate in the development of appropriate strategies for North Texas.

Kimberly Walton, program director of LNT and its parent organization, the North Texas Commission (NTC), said it all came together around a common goal. “People support what they help to create,” Walton said.

One of the highest profile examples of best practice was when DFW hosted Super Bowl XLV through a concerted regional effort. The Dallas Cowboys approached the NTC because it was “Switzerland,” neutral territory, so it didn’t favor any specific municipality. Having a neutral convener is all about instilling trust in the community, Walton explained. The NTC works hard to ensure that its events are balanced, represent all communities in its purview, and build capital with those communities.

Despite the positive examples above, detractors point to fissures in what some characterize as a veneer of regional success. These include regionalism’s propulsion of Dallas’ migrating economic center, dispersing jobs in a way that deepened economic divides and income inequality. Detractors also highlight Dallas’ endemic poverty, crumbling infrastructure, and de facto segregation, attributing these in part to the fact that the city’s and region’s leaders have prioritized a version of economic growth that takes advantage of DFW’s abundant, cheap landmass to disperse new investment across a vast landscape, reaping short-term economic success while ignoring the long-term challenges of sustaining such growth.

Metro is the regional government for the Oregon portion of Portland’s metropolitan area. Formed in 1979, it is the only directly elected regional government and metropolitan planning organization in the United States. Metro’s master plan for the region includes transit-oriented development that promotes mixed-use, high-density development around light rail stops and transit centers and multi-modal transportation investments.

With a broad purview, Metro:

Plans investments in the transportation system for its three-county area and decides how to invest federal highway and public transit funds;

Acts as a regional clearinghouse for land use information and coordinates data and research activities with government partners, academic institutions, and the private sector;

Manages 17,000 acres of parks, trails, and natural areas;

Runs various visitor venues, including the local zoo, convention center, and expo center; and

Plans and oversees the region’s solid waste system.

Metro has a number of advisory committees made up of elected officials, technical staff, and subject matter experts. Most also have seats reserved for members of the community.

Metro’s President Lynn Peterson took office in January 2019 and has focused on addressing the housing and transportation needs of areas outside the region’s thriving city centers. “We’ve done a great job prioritizing the centers, but what makes a transport system work is the entire corridor, not just a downtown,” she said. “That is the next step in where we need to go. It’s the places that connect those centers that we’ve allowed to decay, or just not be used at all.”

Noting that sprawl is bad for the environment and our collective mental health, Peterson believes density is good, with the caveat that it be done well and in the right places.

“Our job is to lead the conversation,” Peterson said. “We can’t solve all of Beaverton’s or West Linn’s problems as a region. They need to step up and solve their own. But we can certainly be part of the investment tool that brings them closer to being able to do more of what they need to accomplish, rather than overbuilding.”

In 2018, voters let Metro borrow $652 million for affordable housing across the region. “It was the first time we’d really passed a regional initiative to address this challenge, and it shows that people understand we have to address these sorts of issues together,” said Metro Councilor Sam Chase. “People understand now that it’s not just one jurisdiction or two jurisdictions; all 27 jurisdictions in our region need to be part of the solution.”